Across the globe, the onset of a new cycle doesn’t always align with January 1st, a date many of us equate with the start of the year. This divergence stems from regional traditions and religious beliefs, some predating the calendar we use today.

Willka Kuti: The Andean Solstice

In the heights of the Altiplano, indigenous communities await the first glimmers of the sun, Tata Inti, yearning for its purifying light to begin the year infused with positive energy. Simultaneously, in the lowlands, they anticipate the appearance of the morning star.

The year 2024, or 5232 according to the Andean-Amazonian calendar, is heralded by these cultures as the dawn of a new era, the era of Pachacuti, signaling a return to the planet’s harmony and balance.

On June 21st, coinciding with the southern hemisphere’s winter solstice, indigenous groups in Bolivia, including the Quechuas, Aymaras, and Guaranís, celebrate the start of their year. Sacred sites like Tiwanaku and the Samaipata ruins become hubs of gathering and festivity.

Enkutatash: The Ethiopian Tradition

Around September 11th, Ethiopia commemorates its New Year, echoing the legendary return of the Queen of Sheba, an event chronicled in the Old Testament.

Enkutatash, meaning “gift of jewels,” stems from a legend where the queen, upon her return, receives a lavish tribute revitalizing the royal treasury.

The day begins with religious ceremonies, followed by family gatherings and the gifting of new clothes to children. Youth actively participate by distributing wildflowers and singing New Year songs, with Saint Mary’s Church on Mount Entoto as one of the most visited shrines.

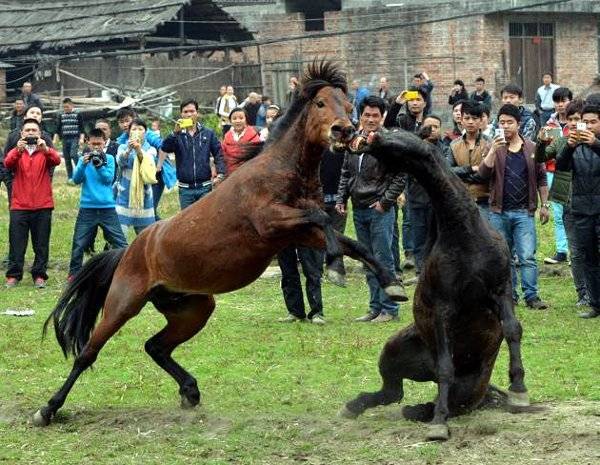

Miao Horse Ritual

In the mountains of southeastern China, the Miao ethnic group celebrates the New Year with a unique tradition: a horse fight.

This custom dates back about 500 years, rooted in a fraternal conflict over a woman’s love, resolved through an equine duel.

Today, these fights are a highlight for villagers and visitors during the spring festival, held in late January or mid-February, though not without criticism from animal welfare organizations.

Samhain: The End of the Celtic Summer

Few in the United States are aware that one of their most popular festivities traces its roots to the ancient Gaelic tradition of Scotland.

Samhain celebrated between the night of October 31st and the dawn of November 1st, marks the end of summer for the Celtic peoples.

This period symbolizes the threshold between the year’s light and darkness. Intriguingly, in the Nanakshahi calendar, followed by Sikhs, March 14th is considered the year’s start, while Baisakhi brings together various Indian religions in a grand annual celebration.

Rosh Hashanah: The Ten Days of Reflection

Jews begin their year on a floating date between September and October, according to their calendar.

Rosh Hashanah, commemorating the creation of Adam and Eve, initiates ten days of introspection known as Yamim Noraim (the “terrible days”), culminating with Yom Kippur, or the Day of Atonement.

During this time, it’s traditional to review the past year’s actions, repent, and forgive those who have caused harm. It’s believed that God judges and grants forgiveness at the end of these days, allowing a clean and renewed start for the year. The shofar, a ram’s horn, is blown before and after Rosh Hashanah prayers, symbolically marking this period.

Baisakhi: The Celebration of Equality

Gobind Singh, the last Sikh guru, established a principle of fundamental equality in 1699, abolishing caste divisions.

Sikhs, primarily concentrated in Northern India and Southern Pakistan, celebrate Baisakhi between April 13th and 14th, coinciding with the harvest season.

Though March 14th marks the year’s start according to the Nanakshahi calendar, Baisakhi is a time of unity for various Indian religions, celebrating it as the onset of a new year.

Songkram: The Festive Water Play

In Thailand, the New Year is celebrated from April 13th to 16th with a distinctive feature: water games.

These games, attracting tourists and locals alike, are particularly popular among children. Traditionally, the last day of the festival was dedicated to honoring the community’s elders and spiritual leaders, pouring a few drops of scented water on their shoulders as a wish for prosperity and gratitude.

This aquatic celebration is not only a time of joy and fun but also a prelude to the rainy season and bountiful harvests. This tradition is also observed in countries like Myanmar, Laos, and Cambodia, marking a time of unity and renewal.