Voodoo, a religion with deep African roots, has notably evolved in Haiti and Louisiana. In Haiti, syncretism with Catholicism allowed enslaved people to preserve their beliefs under the guise of saints, giving rise to a rich tradition of loas such as Papa Legba and Erzulie Freda. In Louisiana, the blend of French, Spanish, and Creole influences has generated unique practices, such as the use of gris-gris amulets and voodoo dolls, reflecting a resilient and diverse cultural adaptation.

Voodoo Traditions: From West Africa to North America

To begin, it is important to highlight that voodoo has transcended borders and centuries, merging African beliefs with Catholic practices and local traditions. This religion, rooted in the experiences of enslaved people brought from West Africa, has spread throughout the Caribbean and parts of North America, acquiring unique nuances in each region. Its complex network of deities, rituals, and symbols constitutes a culturally rich mosaic where the ancestral and the modern converge.

Additionally, it is important to understand that voodoo has its roots in ancient African religions, particularly in the region of Dahomey (modern-day Benin).

During the colonial period, enslaved people brought to the Caribbean combined their original spiritual practices with Catholic elements, creating a syncretic form of worship. In this way, the loas—or spiritual entities—merged with the veneration of saints, cloaking African beliefs under Catholic icons to evade persecution by colonizers.

Theological Structure and Main Loas — Religious Syncretism and African Legacy

The theological foundation of voodoo revolves around a supreme god named Bondye (also known as “Good God”), who remains distant from humanity. Consequently, practitioners establish connections with the loas, considered intermediary forces capable of influencing daily life.

Among these, Papa Legba holds a prominent place: he acts as the guardian of crossroads and mediator between the human world and the divine. Other notable loas include Erzulie Freda, a symbol of love, and Simbi, associated with magic and witchcraft. Additionally, Kouzin Zaka represents agriculture and fertility, reflecting the need for subsistence in rural environments.

Likewise, syncretism is not only manifested in the assimilation of loas with Catholic saints but also in songs, dances, and ritual languages.

Haitian voodoo, which emerged in the 16th century on the island of Hispaniola, made syncretism a strategy for cultural survival against colonial oppression. This integration allowed practitioners to camouflage their gods behind Christian figures, keeping the essence of their African rites alive.

In the case of Haiti, the worship is divided into various families of loas, including Rada and Petro, which represent opposing poles: Rada evokes calm energy and prosperous African roots, while Petro embodies fury and the desire for liberation stemming from slavery.

Distinctive Features of Louisiana Voodoo — Voodoo Dolls and Associated Practices

On the other hand, Louisiana voodoo presents a cultural melting pot that integrates French, Spanish, Catholic, and Creole elements, resulting from the convergence of African slaves with the local population. Within this tradition, the use of gris-gris amulets stands out for their protective function.

These small bags contain oils, hairs, bones, and other personal materials, typically worn on clothing or around the neck. They are believed to provide defense against negative forces and ensure good fortune. Similarly, the so-called “voodoo queens” play a central role in ceremonies and dances, symbolizing female leadership and connection with spirits.

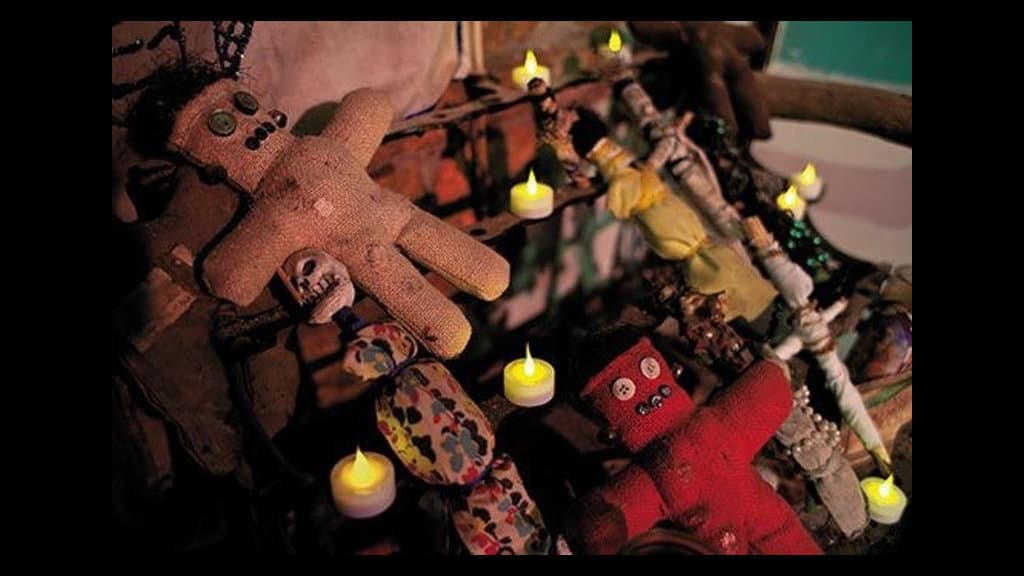

One of the most media-highlighted aspects of voodoo lies in the use of dolls for magical purposes. Although popularized as instruments of harm, these effigies are linked to sympathetic magic: they are made to represent specific individuals so that any action performed on the doll—whether piercing with pins or applying heat—has a reflective effect on the targeted person.

This practice is also associated with hoodoo, a parallel tradition where similar principles of witchcraft and sorcery coexist.

The Spirit of the Serpent and Its Symbolism

Another essential element in Louisiana voodoo is the veneration of Li Grand Zombie, considered a manifestation of the serpent Damballah, an African deity associated with health and cosmic harmony.

The symbolism of the serpent reinforces the union between earth and sky, representing the continuity of life and ancestral wisdom. Thus, this spiritual figure synthesizes African heritage and the cultural adaptation experienced in the New World.

The richness of voodoo lies in its ability to keep the memory of Africa alive while adapting to new environments. Beyond the fascination it arouses for its esoteric aspects, this religion expresses the hope and protection of communities that have faced centuries of oppression.

Understanding its origins, its loas, and the symbolic strength of its rituals allows us to appreciate the complexity and vitality of a tradition forged in resilience and transformation.

Mike Rivero – Esoteric News and Voodoos