Nestled in the heart of Lima, the Convent of San Francisco and its catacombs stand as a beacon of Peruvian history. Dating back to the 16th and 17th centuries, this complex is not only a testament to the Christian faith but also a reflection of the cultural fusion that is quintessential to Peru. As visitors wander through its cloisters, churches, and catacombs, they are immersed in an era where art and religion are deeply and meaningfully intertwined.

The Convent of San Francisco in Lima: A Treasure of Art and History

The striking towers, painted in a vivid yellow, and located in Lima’s monumental zone, are renowned for their architecture. They frame a dark stone altarpiece portal, at the center of which stands a sculpture of the Immaculate Conception.

The main portal of the Convent of San Francisco, one of the three largest in America, is adorned with a filigree medallion representing the symbol of Christ. Encompassing a whole city block in the center of Lima, the convent reflects the architectural splendor of the 16th and 17th centuries, designed to awe and influence the indigenous people towards the Christian faith.

Entering the convent reveals the mysteries held within its robust walls. The tour, permitted only in guided groups, provides a journey through centuries of Lima’s history. The first surprise is upon ascending the staircase: a Mudéjar-style dome from Seville, carved in cedar wood at the end of the 16th century.

The Mudéjar Style

Originating from southern Spain, the Mudéjar style was developed by Morisco architects and artisans following the Christian reconquest. Drawing inspiration from Islamic forms and decorations, this style was embraced by many Christian princes.

Due to the Islamic prohibition of depicting humans or animals in art, Mudéjar decorations predominantly feature floral and geometric patterns. In tiles and coffered wood ceilings, the star symbol is a recurrent motif.

Calligraphy with Quotes from the Quran

Mostly Muslim master craftsmen incorporated calligraphy with Quranic quotes into the plaster or stone decorations of many buildings. Thus, in numerous Christian palaces and some churches in Spain, Arabic inscriptions such as “Allah is great” are found, often unbeknownst to the Catholic sponsors.

The three main centers of Mudéjar art in Spain were Seville, Teruel, and Toledo. Its golden age spanned from the late 13th century to the early 17th century, though there was a revival, the “Neo-Mudéjar,” in the 20th century.

We ascend to the impressive library, one of the most modern and significant in 17th-century America. Its shelves of fine wood house valuable manuscripts, prayer books, and theological treatises, all battling time and decay.

The library also contains books in Quechua. Unfortunately, entry to its rooms is not permitted; they can only be observed from the entrance.

Main Church of the Convent

Ascending to the upper part of the Convent’s main Church, we are greeted with an excellent view of the basilica, whose lateral naves consist of chapels. The columns, vaults, and the central dome, showcasing a style more Mannerist than Baroque, are adorned with geometric motifs in red and white.

Unlike Baroque churches in Lima, such as La Merced and San Pedro, the Church of San Francisco is simpler, devoid of the towering altarpieces typical of the Churrigueresque Baroque. Nevertheless, this church and the extensive complex of the Convent of San Francisco house more artistic treasures than the Lima Cathedral.

Wandering through the sacristy and the chapter house, visitors can admire works by Francisco de Zurbarán, a prominent painter of the Sevillian School, sculptures by Alonso Cano, and other ‘imported’ Baroque masters. It’s almost miraculous that these artworks have arrived here, evading English pirates and surviving storms in an era brimming with adventure.

Holy Supper of the Cuzco School

In Peru, a painting from the Cuzco School depicting the Holy Supper stands out. This immense work portrays Jesus and his apostles, with the unique feature of Jesus blessing a guinea pig instead of the traditional lamb.

The rooms of the Convent of San Francisco in Lima house an impressive collection of first-rate art. Despite this, for many visitors, the most striking aspect lies in the convent’s subterranean world.

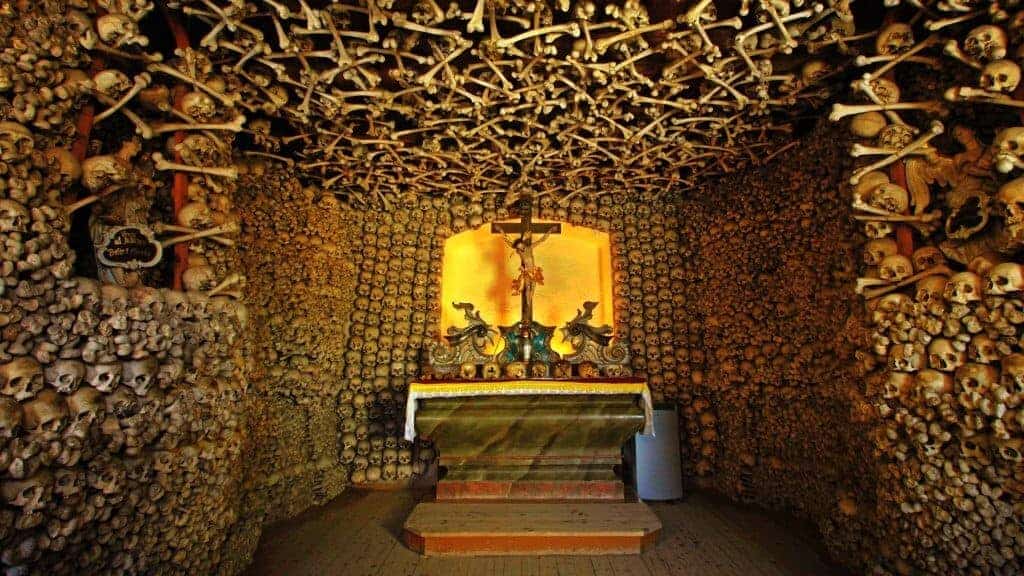

We bravely reach the catacombs, a dark labyrinth of tunnels. As our eyes adjust to the dim light, we discover immense pits filled with skulls and human bones on both sides of the narrow path, almost within reach of our feet.

The group’s reactions vary from screams of fear to nervous laughter and defiant whistles toward death.

Tunnel of the Dead

In the “Tunnel of the Dead,” some visitors are rendered speechless by the sight of human fragility, while others, more composed, are entertained by the eerie scenes in this subterranean cathedral of bones.

To heighten the drama, some pits feature skulls and bones arranged in geometric shapes, creating circles of skulls that seem to watch us with their empty sockets.

Far from being a mere tourist attraction, the catacombs of San Francisco served as the main cemetery of Lima during the 16th and 17th centuries. It is estimated that around 70,000 inhabitants of the capital were buried here.

Today, this underground site seems to have lost its silence and peace, as Lima seeks to attract tourists in search of spectacular and unique experiences.

Catacombs of the Convent of San Francisco

Here, 70,000 skulls glimmer under the flashes of cameras from excited visitors. The souls of the deceased resting here are likely undisturbed by the presence of the living. On the contrary, they might watch with some amusement as mortals attempt to overcome their fears by photographing or ridiculing death.

At the end of the tour, the group, relieved like children after a thrilling ride, follows the guide back to the light, leaving behind the darkness of the catacombs. Before parting, the guide shows us another artistic gem: the Convent’s Cloister, almost entirely adorned with a baseboard of gleaming tiles.

The Carthusian Monastery

What’s extraordinary about these tiles, some dated 1620, is their origin: they are from the famous La Cartuja ceramics factory in Seville.

Transported to Lima through a long and perilous sea voyage, they are now carefully restored to preserve the memory of the city. We stroll through the cloister, admiring the images on the tiles that sometimes depict surprisingly secular figures.

We bid farewell to this architectural complex, an open book of the history of the “City of Kings.” Seated in the sunny plaza in front of the Church of San Francisco, we watch children playing and chasing pigeons around the fountain.

It’s intriguing to ponder if they know that, just beneath their feet, lie the skulls of their ancestors.

The visit to the Catacombs of Lima concludes, but the impression it leaves is enduring. These underground passageways and the Convent of San Francisco are a mirror of the history and culture of Peru, an invitation to reflect on the past and appreciate the art and architecture that have survived through the centuries.

It’s an experience that enriches and educates, showcasing the depth and diversity of Lima’s legacy.