Spain extends a hand to the descendants of Sephardic Jews exiled more than five centuries ago. The approved legislation aims to heal wounds, restore cultural ties, and offer citizenship to those who kept the memory alive. This symbolic gesture reflects an effort to acknowledge past mistakes and strengthen bonds with a global diaspora.

Spain Offers Citizenship to Sephardic Jews: A Reunion with History

Spain, which in 1492 expelled thousands of Jews after centuries of coexistence, has begun to settle accounts with its history.

For several years now, the Spanish government has been implementing measures to grant citizenship to the descendants of Sephardic Jews, those whose roots trace back to the Iberian Peninsula before the Inquisition.

This gesture, rich in political, economic, and cultural symbolism, seeks to close a wound that has remained open for more than half a millennium. At the same time, it raises complex questions about identity, faith, and the intercontinental ties that connect communities scattered around the world.

A Legacy Forged in the Diaspora

By the late 15th century, around 300,000 Jews lived in Spain, forming one of the most prosperous and influential communities in Europe.

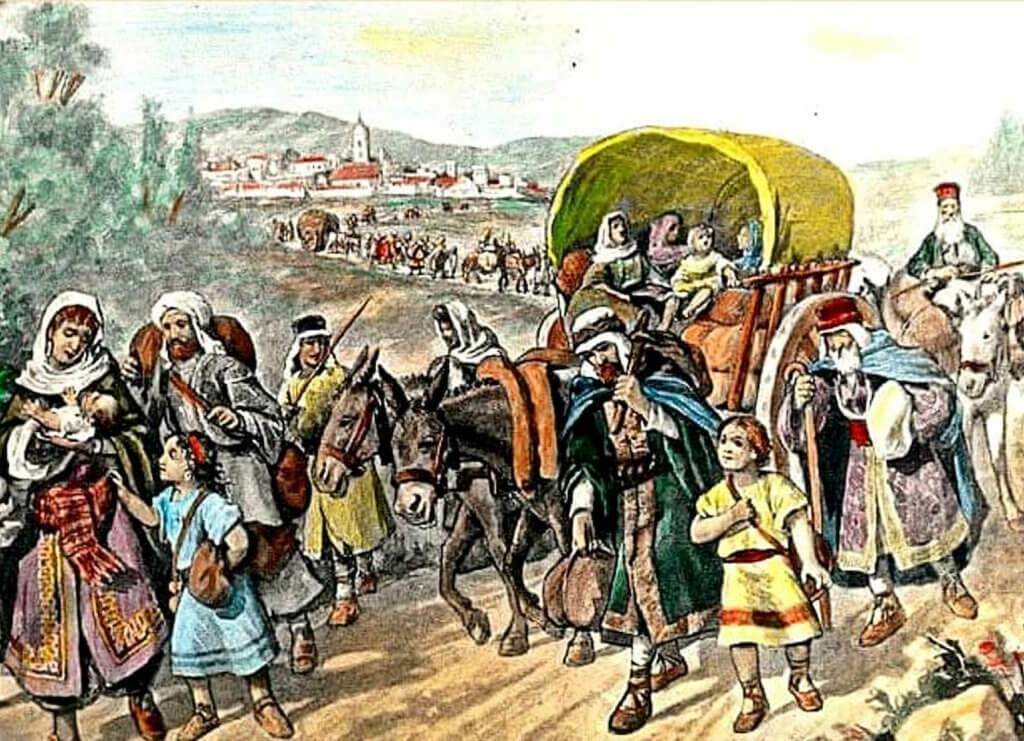

After the issuance of the Edict of Granada in 1492, which forced Jews to convert to Catholicism or go into exile, it is estimated that about 100,000 left for new horizons. The families who departed took with them customs, stories, surnames, and a unique language, Ladino, inherited from medieval Castilian.

Thus, they formed new communities in territories as distant as the Ottoman Empire, North Africa, and parts of Eastern Europe.

Over time, Ladino became a symbol of a shared past, a language that survived through oral transmission across generations. However, with modernity and globalization, it has weakened, now at risk of extinction.

Nevertheless, the notion of Sephardic origin did not fade: entire families have preserved their oral histories, documents, and surnames that indicate Iberian ancestry. Many descendants, even non-practicing ones, feel an emotional connection to the land their ancestors were forced to abandon.

The New Law and Its Implications

In 2015, Spain passed a law granting Spanish citizenship to the descendants of Sephardic Jews without requiring them to renounce their original citizenship, provided they could demonstrate their historical ties to the expelled community.

This initiative arose from the intention to recognize historical injustice while reconnecting with a diaspora that remains vibrant, especially in countries like Turkey, Morocco, France, the United States, the United Kingdom, Brazil, and Mexico.

The regulation, which remained under development and adjustment for several years, simplified the path to citizenship. Although the process required documentation, proof of surnames, family ties, and certification from the Federation of Jewish Communities of Spain (FCJE), the response was massive.

When the news broke, thousands of descendants expressed interest: from Turkish families preserving prayers in Ladino to American professionals who had only recently discovered their Sephardic heritage. According to unofficial data, initial inquiries exceeded six thousand within the first month of the announcement.

Religion, Identity, and Citizenship: A Complex Debate

The law, however, did not escape internal debates. Many applicants do not consider themselves practicing Jews, nor do they maintain an active religious life.

Their ancestors, forced into baptism, became converts to survive persecution. Therefore, some descendants faced questions: Should they return to the Jewish faith, or would their historical lineage suffice? Is religion an indispensable condition for reclaiming citizenship?

The regulation attempted to clarify these doubts by specifying that family tradition, surnames, language, or membership in Sephardic cultural institutions could serve as evidence. However, some felt they needed to go a step further. For some, reuniting with Spanish citizenship represented a poetic act that closed a circle. For others, it required a religious conversion that reopened old tensions about freedom of belief.

Academic sources indicate that the final version of the rules aims to be as inclusive as possible. Beyond religion, the essential factor lies in historical and cultural ties. The details, adjusted over time, seek to avoid repeating past religious coercion. Today, following the official application period that ended in 2019 for this special citizenship route, the time has come for analysis: How many benefited? How does this measure impact the contemporary identity of Sephardim?

Economic and Geopolitical Dimensions

The Spanish government’s motivations are not limited to moral or historical concerns. Some analysts argue that recognizing citizenship for Sephardim could provide an economic boost, as many applicants are entrepreneurs or professionals willing to invest.

In the past, the expulsion of Jews had severe economic consequences. According to accounts of the time, the Sultan of the Ottoman Empire himself expressed surprise that a monarch as powerful as Ferdinand of Aragon would allow a community that contributed wealth and trade to leave.

Some experts question whether, in the current context—marked by economic instability, the departure of young talent, and the search for foreign capital—the initiative to attract Sephardic descendants also responds to practical calculations.

However, other historians point out that, given Spain’s economic crisis over the last decade, the real impact of these new nationalizations on the economy has been moderate. In any case, the measure is interpreted as a symbol of openness and recognition of a cultural diversity that was once suppressed.

The Role of Historical Memory in Contemporary Spain

Reconciliation with the past is a process Spain has faced for decades, not only regarding the expulsion of Jews but also in relation to other complex historical episodes.

This symbolic return of Sephardim fits into a broader trend: recovering memory, acknowledging mistakes, apologizing, and offering restitution where possible. This gesture, far from being merely symbolic, represents a step forward in building a society that values pluralism.

Furthermore, critical voices point out that the invitation to Sephardim contrasts with the situation of other expelled or persecuted groups, particularly during the same historical period, such as Andalusian Muslims. Why does restitution come for some and not for others?

This question is frequently raised in academic forums, where some scholars recommend that the Spanish state expand its examination of the past to other historically marginalized minorities. However, the Sephardic case garners attention for its cultural significance, the symbolic weight of the diaspora, and the broad international resonance of the process.

Ladino: A Linguistic Bridge with Five Centuries of History

One of the most valuable cultural treasures inherited by the Sephardic community is Ladino, a language with an ancient Castilian structure, enriched with Hebrew and words borrowed from the places where Jews settled after the exile.

Although it has been in decline, some families preserve expressions and songs that connect them to medieval Spain. Revitalizing Ladino is not just a linguistic effort; it is, above all, an identity anchor that demonstrates how centuries have not erased the sense of belonging.

The new generation of Sephardim, dispersed in countries with dominant languages, maintains an interest in their roots. For many, obtaining Spanish citizenship means reconnecting with a past that seemed legendary. The newly granted citizenship offers the possibility of establishing homes, businesses, and even being buried on Spanish soil, thus closing a vital cycle.

Some have acquired land, others have initiated formalities, and many reflect on the emotional value of holding a passport that finally symbolizes the acceptance of a heritage marginalized for centuries.

Toward an Inclusive Future

Today, as Spanish institutions reflect on the impact of this measure, the Sephardic community continues to play a role in memory politics, cultural diplomacy, and the mutual enrichment between Spain and the world.

This invitation to citizenship is not just a legal act but a reaffirmation that the past can dialogue with the present, offering new interpretations and opportunities. The return may not translate into masses relocating to the Peninsula, but the gesture cements emotional, historical, and symbolic bridges that reinforce the nation’s plural identity.