In post-World War II Spain, amidst widespread poverty and despair, there was a significant wave of emigration from the Canary Islands to Venezuela. Men journeyed across seas with the hope of securing a better future, leaving their wives and children behind. These women, embodiments of strength and resilience, penned letters that painted a vivid picture of their austere reality, yet always infused with a sense of hope and faith.

Resilience and Faith as Pillars in Challenging Times: Remembrances from Post-War Spain

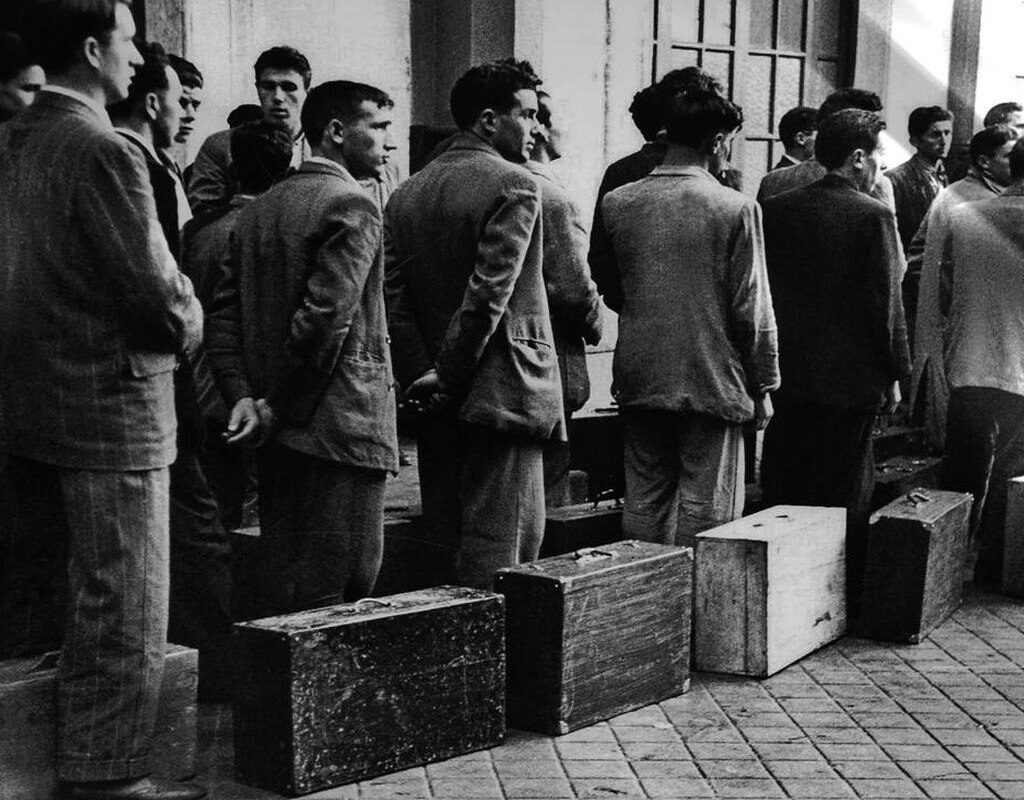

Men departed in the hushed tones of dawn, either covertly on humble boats or clutching their prized travel documents, safeguarded as if they were golden treasures nestled within empty crates.

Upon completing the voyage, an uncertain promise awaited them. Some discovered prosperity and never returned, while others were less fortunate and came back burdened with the weight of failure, which seemed to haunt their every step. They left behind their wives and children, who, like mourners trapped in a never-ending vigil, visited our homes to dictate letters, attempting to encapsulate the reality unfolding in their absence.

They dictated each word with the solemnity of a final testament, detailing their daily struggles. Each letter commenced with a common phrase:

“Dear husband, I pray you are in good health when this letter reaches you. We are well here, thank God”.

As the letters unfolded, the harsh realities of poverty, sickness, and death emerged. As a young adolescent, I transcribed the tremors of their lives with my pen and then read their words back to them. They entrusted me with the accuracy of their accounts, validating my transcription with a scribbled signature beneath my writing, affirming their authorship.

This was the reality of Spain, ravaged by a war that was fought far away but left its moral scar on the island, forever changing the lives of its inhabitants. Some emigrated, while others remained, weaving narratives of everyday scarcity.

Remittances of Hope: How Venezuela Transformed Our World

One day, my Uncle Tomás, one of the emigrants, showed up at our doorstep. He had found employment with Leche Carabobo, located in Colinas de Bello Monte – a familiar address from the envelopes of those poignant letters. The day following his visit, a gas stove, a novelty of such significance, arrived at our home that we had to learn its operation.

Gradually, other households began to receive gifts from Venezuela, alleviating the pervading hardship. Years later, I would find the phrase “Thank you, Venezuela” indelibly etched onto a house in El Hierro.

One day, a book, the first to ever grace our household, arrived from Caracas. Although the financial support was delivered through other channels, it was Venezuela that eased the pervasive sense of desolation triggered by the poverty from which those letters had originated.

Everyone is well here, thank God

Today, the circumstances are vastly different.

Venezuela now signifies a festering wound in Spain’s heart. It’s impossible not to recall the tragedy reflected in those letters – disease, medical scarcity, poverty, death. The political hesitation to address Venezuela brings to mind the voices of those women recounting the gravest tragedy of our era.

No, the letters did not conclude in this manner. And the correspondence from Venezuela cannot conclude this way today either. Despite attempts to muffle the truth of Venezuela’s current condition, as though it’s not a part of our shared history, the pain it induces and the solidarity its present predicament inspires among those of us with roots there, cannot be erased, even if it’s merely through letters.

This analytical piece is a rework of an original by the esteemed Juan Cruz, a native of Puerto de la Cruz (1948). Cruz is a well-respected journalist, writer, and editor, who studied Journalism and History at the distinguished University of La Laguna. His original piece was published in the widely-recognized Spanish newspaper, El País.